- The Concannon family in the farmyard in Montiagh, 1950.

- Persse’s distillery, in the early years of this century, had their own buyer at the Galway market, a Martin Cullinan from Claregalway, whose task was to buy good quality oats and barley.

Claregalway has been and continues to be largely a farming community with its rich limestone soil ideal for tillage farming and grazing for stock and other animals. The typical size of the farms in the parish varies from twenty to seventy acres.

Farmers kept pigs and cows. Some also kept some sheep, horses, turkeys, geese and chickens. The fowl were kept to produce eggs, which would be consumed for home use or sold at the fair. It was mostly dry stock in Claregalway but some farmers did produce milk. In the olden days, all milk was consumed at home; either drank fresh or let go sour and churned into butter. In the last 30 years or so most milk has gone to the creamery either in Renmore or Athenry.

When land was being valued in the last century, the land of Carnmore was valued at a lower level than other land in the parish because of the fact that there was not much water or wells on the land. The land itself though was probably better than the higher valued land in the west of the parish and since the 1973 water scheme, Carnmore now has an adequate water supply.

Grievances over land were particularly liable to erupt into violence. In 1837 in Claregalway when tenants were evicted from the Lord Clanmorris estate, the man who took over possession was targeted. He himself was beaten “most unmercifully” as was his son, while their workers, who were ploughing at the time had to run to safety leaving their horses to be chased off the land, and the implements to be broken by the mob. When the Loughgeorge police arrived they saw some distance away on a hill a large number of people shouting and hollering.

Pigs

Every farmhouse had a pig or two usually a sow and some bonhams. They were easy to keep as they lived on scraps and people generally let them roam around the farm during the day. Up until the 1960s pigs were either sold in the markets or else killed at home, but after that they were sent to the slaughterhouse in Galway.

Pig markets were held at Lenihans, now “the Nine Arches” pub. Lenihans pub was at the site of the fair in Claregalway, and it seems that it was the fair that brought about the pub and not vice versa. Some of the buyers at Lenihans were McGiverns (who had stores in Galway and Monivea) and the Glynn brothers. James Healy bought pigs in Hessions pub during the summer.

There was also a pig market at Loughgeorge where the weighing, buying and selling occurred. Corbett, another very popular buyer from Headford would visit Loughgeorge on a Monday. There was also another buyer named Kelly who visited Loughgeorge. Most of the pigs fetched 15 shillings or so and went on to the Castlebar or Claremorris factories. Occasionally the farmers sold their bonhams in Galway. As was stated earlier pigs were killed at home for food and although a Mr. Donovan from Mullacuttra was a well-known pig killer, every village had somebody who could be called upon when needed.

Beet

Beet was first grown as a serious cash crop in 1933 and despite the hardships that were initially related to achieving a good yield, it continued to be grown until the Tuam Sugar Factory closed in 1984. That is not to say that the odd farmer doesn’t still plant beet, but no longer is his shoulder strained as regularly as of old with carrying loads of sugar beet.

Back in the 1930s a horse machine was used to sow the beet but this was a luxury compared to sowing by hand. Billy Morris, Cregboy recalled how he was “on his knees all the time” one summer singling and weeding the beet. Another hardship he recalled was when he had to fill the lorry by hand, as there was no beet fork. The beet was weighed in Oranmore Station and fetched over 30 shillings a ton. An advantage in growing beet was that the pulp was returned to the farmers who made good use of it, feeding it to calves and sheep. During the war, beet farmers were fortunate during the rationing as the Sugar Factory gave them permits to buy sugar. The final advantage to the beet growers was that they were always guaranteed a fixed price.

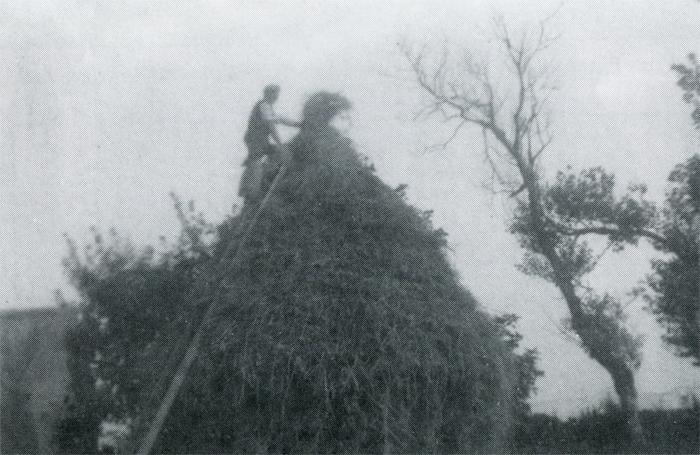

Turf

The bogs in Claregalway are located in the townlands of Cloon, Curraghmore, Gortcloonmore, Waterdale and as its name suggests, Montiagh. One man who had a bog in Gortcloonmore described the old procedure, which was used in the days before the turf machine. Parties of three were necessary for a successful day. The first, a cutter would go down with his “slean” and cut the sods and throw them up to the two spreaders who would fill a barrow with 10-12 sods, wheel it out and spread the turf out flat where it was left for a fortnight. After this it was put standing in “groigins” and eventually brought home in carts and creels. Generally the turf was cut once a year but this was changed to twice a year during the Emergency. When the people from Montiagh had no other work, they used to travel to Oranmore nearly every second day to sell their turf.

Eggs & Fowl

Many people kept fowl as they could throw scraps to them or just let them pick. Hens, geese, chickens and turkeys were to be found to varying degrees around. The belief was “more poultry, better woman,” so anyone who had their gaggle of geese was doing well. At the time of the pig markets near the castle, women from Gortatleva, Ballymurphy and other areas brought large baskets of eggs to these markets to sell. One women remembered a lorry coming from Athenry once a week to buy these eggs. There were people who sold sugar and tea at the markets so if all the eggs were sold you could buy a pound of one or the other.

Horses

Not all farmers in the parish had horses but nonetheless, there were a few in each townland and consequently the machinery of the time was all horse-drawn. It is known that all the big houses had horses. The farmers who had to do without were lent horses and also whatever implements they needed. In the 1920s and 1930s some of these included horse ploughs, harrows, reapers and binders. For hay, there was also a horse-mowing machine, but the horses weren’t too keen on it, as it was noisy and uncomfortable. This mower could also be adapted for cutting corn. Various attachments were added and the driver used to sit up on a seat with a rake, which he used to lay the sheaves.

A number of people in the parish remember the races at Loughgeorge which mainly consisted of common working horses and lasted for about two days. In 1906, the Galway Committee of Agriculture offered nominations to farmers mares to be served by thoroughbred stallions. The value of each nomination was £2. Preference was given to the best young mares under six years of age. Each mare had to be the property of a farmer whose holding did not exceed a valuation of £300, but three-fourths of the nomination was reserved for farmers under the £30 valuation. Claregalway got 17 nominations.

The horses of Claregalway achieved certain notoriety in 1929 when the Connacht Tribune stated that they “could not make any hand of tarred roads.” Mr N Kyne spoke on behalf of the Claregalway farmers, many of whom were present in the public gallery, saying that horses could not draw loads over the tarred half of the road, so that they all had to travel on the sanded half. Horses shoes could be “sharpened” for 3s. to travel on tar and unsharpened afterwards for another 3s. but this was both expensive and time consuming. Tarred roads suited lorries, cars and buses and the county surveyor said it was hard to reconcile the two forms of traffic. It was also felt as strange that it was only Claregalway horses, which seemed to have a problem. The situation was so bad that at areas near Holmes Hill and Rockwood the council had placed empty tar barrels to stop horses using one side of the road only!

Crops

Oats were grown in all parts of the parish and were thrashed, originally by flail. The flails in Claregalway were as others made from hazel and holly joined together by a leather thong. In some places it was called a “suist”. After thrashing came the winnowing and this involved letting the oats fall in a windy shed. The wind blew the chaff away and the heavier seed fell straight down, where it was gathered later. Some people had a winnowing machine, which involved putting oats in and then turning the handle, but nobody seemed too keen to praise this particular machine. Originally thrashing was a community effort but many of the labourers that used to get work in Claregalway were let go after mechanisation.

Ploughing

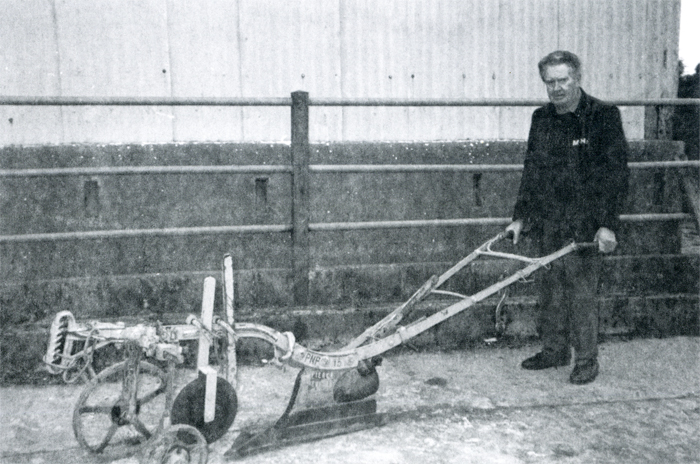

Thomas O’Reilly from Cloon, Claregalway first started ploughing in 1945. Ploughing was very popular at the time as can be seen from the numerous articles in the Connacht Tribune. Mr O’Reilly recalls that up to 50 or 60 teams of horses would compete in the competitions. There were quite a few from Claregalway involved in the ploughing at county level.

He has won 28 county senior matches. He won the Junior All-Ireland in 1963 and 10 Senior All-Irelands in 1978, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1988, 1989, 1991 and 1993. He also won a special horse class in 1990 and 1992. He represented Ireland in the 1984 World Ploughing Championship, which were held in Horn Castle, Lincolnshire, England, where he was runner up. In the Championship the competitors ploughed for two days, then after that marks were given. The World Ploughing Championships are held in different places all over the world each year. He was placed third in the European ploughing championships that were held in Limavaddy, Derry in 1991.

Thomas O’Reilly explained how the condition of the field plays an important part in ploughing. Also he told us that in the beginning he used to borrow horses for the competition but as he “went at it in earnest” he purchased his own. Now his son Gerard is also involved in ploughing. Pat Kilgarriff composed the following poem to the ploughman’s daughter on her wedding day:

The Wedding

It was up in Claregalway at a wedding one day,

Some came for to look and some came for to pray,

It was James Kilgarriff who built in Rahoon,

And Tom Reilly’s daughter, the ploughman from Cloon.

Now Jimmy took Mary and Mary took Jim,

And pictures were taken of her and of him,

You could tell by his smile he was over the moon,

With Tom Reilly’s daughter, the champion from Cloon.

We left from Claregalway to drive into town,

And bonfires were blazing around Cahergowan,

We drove into Galway our bellies to fill,

At a place called the Warwick away up in Salthill.

They were singing and dancing and screeching for more,

They knocked lights off the ceiling and sparks off the floor,

They were ploughing with horses around Galway Bay,

And Pat Murphy’s meadow was mowed in a day.

They sang of the Claddagh at the foot of Fairhill,

With everyone happy and Tom paying the bill,

Then we departed to give Tom his due,

The All Ireland trophies at a pub in Cloonboo.

Fairs & Markets

A fair existed in Claregalway in the nineteenth century. Proof of this is contained in the Connacht Tribune of 1852, which tells us that the fair day was set for the 12th October. Here people bought and sold bonhams, cows, sheep, cattle and every sort of vegetable as well as oats, wheat and barley. Besides this, the people of the parish travelled to fairs in Galway, Athenry, Tuam and Headford. When the people had to go to Galway this meant leaving home at one or two in the morning to walk to the fair with their livestock. As people didn’t have good lights at the time the journey was even harder.

When they arrived in Galway they had to find a place to stand with their animals, anywhere from where Moons is now, all the way out to Bohermore. In the late 1950s cattle and sheep were sold here, and occasionally bonhams, as mentioned earlier. Other produce sold in Galway were oats, turnips and potatoes that were usually brought into town on a horse and cart. There were usually sold opposite the American Hotel, as there was a scale there for weighing. A strange practice at the time was that it was often incumbent upon the seller to deliver the produce, which meant that the day was made even longer as all the different runs had to be made. Also sold was the rye that was grown in the boggy land, straw which was good for thatching and cart loads of hay. When everything was sold and the day was over, everyone headed for home.

McDonaghs and Palmers were two big oat buyers at the markets. When Martin McDonagh was the most extensive merchant in Galway he employed a man from Claregalway to buy oats for him. A certain story went around that this man used to walk around the sellers with his hands behind his back and if someone “tipped” him some money, McDonaghs would buy their oats. Mr McDonagh, or Mairtín Mór as he was more commonly known, also employed Sean Corcoran from Lydacan to look after his horses.

Persse’s distillery, in the early years of this century, had their own buyer at the Galway market, a Martin Cullinan from Claregalway, whose task was to buy good quality oats and barley.

One man from Claregalway gave an account of his memories of the fairs in Galway:

“There was a weighing scale in the square in Galway. It is gone out of it now. They had a great name in our village for having a top class potato. I used to hear my father and my brother say that they wouldn’t be allowed pass through Bohermore but they’d have the whole lot of the potatoes sold before they got to the market at all.”

Another person recalled how a lot of bargaining went on between the buyer and the seller to get the best possible price going. Finally when the deal was struck (by spitting on the palm of the hand and shaking hands) the farmer would give the buyer a little “luck money”. Then they both proceeded to the pub for a drink.