The River Clare rises in Ballyhaunis, Co. Mayo, and is roughly 85km in length. It passes through Dunmore and Milltown and the neighbouring parish of Lackagh before entering Claregalway, and continuing to Lough Corrib.

The Clare is used as a boundary mark for many of the townlands in the Claregalway parish. Kiniska is the first townland to the north of the river. To the south of the river is Gortatleva and next to this is one field in Lydacan. The townland of Lakeview runs along with the river, out on to the N17. On crossing the road it divides Cahergowan from the Claregalway townland. After this it forms the dividing line between Montiagh North and South. Curraghmore is located to the north. Finally the river pours into the Corrib.

Clár an Diabhail

The first mention of a bridge over the Clare in Claregalway was in 1349 and was probably a wooden structure. The Nine Arches were erected in stone probably in the early 1700s. Though this bridge is not still in use, it is a very impressive sight and an attractive reminder of Claregalway’s past.

Prior to this bridge, the Clare was crossed by planks, and was very treacherous to get over, giving Claregalway its original name, Clár an Diabhail or Devil’s Flat. Poet Edward Coppinger wrote the following poem in 2012, which describes the search for a young girl who was swept away by Clare’s current during a flood. It also relates some local folklore, about “grim Clare” taking life every seven years.

The River Search

It was the sky made our river grow,

Faster and faster became its flow,

From the teeming heavens came

A deluge of torrential rain.

Higher and higher rose a flood

Of water, that brought no good,

As high as no one could compare

A demon became the River Clare.

Its powerful force was hell bent

In menacing malevolent evil intent—

With angry foaming churning water,

Took the life of John James’s daughter.

Older men would often relate

About a curse in that rivers spate,

And of misfortune bringing tears—

Taking life every seven years.

On the banks wet and wild

Vigil was kept for the missing child,

A search machine placed on the deep—

Was a blessed candle on a sheaf!

Prayers and Blessing said and done

The ancient ritual then begun,

And from the safety of the side

The sheaf was launched on the tide.

Floating fast then slowing down,

Beyond Lackagh bridge to Salmontown,

And in the current rapids change,

Quickly passed the bridge of Grange.

Drifting beneath Cregmore bridge,

Strange and surreal its pilgrimage,

At a slow meandering pace

To find grim Clare’s hiding place.

Thrice the sheaf spun round & round

Over deep and dark Poll Domhain—

That God’s hand did guide and steer,

Her young body was found here.

In a graveyard below the hill

By the ruin of Columcille,

Once stood a lonely wooden cross

Telling the story of her loss.

Our old men are no longer there,

They sleep now by the Clare,

Who knew well our rivers tears,

That took life every seven years!

Flooding & Drainage

Flooding has been a constant problem in the Claregalway area over the centuries, mainly because of the flat and low-lying terrain, and of course the West of Ireland rain. Numerous attempts were made at drainage, either through changing the course of the Clare or deepening it.

In 1954 the largest arterial drainage scheme of its kind ever undertaken in this country commenced. This was known as the Corrib Drainage Scheme. It benefited farmers in Galway, Mayo and Roscommon and the Clare River and its tributaries came within the scheme. Four hundred miles of river and stream were widened and deepened to carry water off an area of four hundred square miles of land.

Transport

River transport was mostly on the lower stretches of the Clare, from Claregalway to Lough Corrib. The transport of turf accounted for the major part of it, but the Claregalway boatmen also took part in the general trade on the lake. Many of them were from Montiagh with about 40 boats in all from that village. They used flat-bottomed boats called ‘flats’. These were about 17 feet long and were designed to carry a load on shallow water. The boat would be pushed along with an ash pole about 8 foot long called a ‘cliath’. They were very stable and safe although there was a story mentioned about one such boat that sprung a leak and the occupants had to save the turf by throwing it onto the bank, before saving themselves, which they did.

Boats returning home to Claregalway had difficulty in finding the mouth of the Clare, as the shore of Lough Corrib around that area was overgrown. A long pole was set up at the river mouth to help in guiding the boats in.

Fishing & Poaching

Fishing has long been an important practice associated with the River Clare. However many people have not always been strictly within the law, regarding this. The fact that some people reverted to poaching may have been as a direct result of the fishing restrictions that existed. For the people of Montiagh, fishing and the sale of turf was their livelihood. The river was noted for salmon poaching, for the locals, knowing the pools where the fish rested at night, easily caught them with nets. The salmon were nearly always sold, much of it in Galway city.

The fishing rights from the Claregalway bridge to the lake belong to the Castle owners, as do those on the Castle side above the river. The rights on the opposite side of the river belong to the farmers. Some farmers bought fishing rights and later sold them or rented them to angling clubs.

According to local accounts, poachers would seek out deep areas, with few rocks, with one man going on each side of the river. They used nets like those used at sea. They would organise a lookout so that if the Gardaí or bailiffs arrived the nets would “disappear” to safety. In the 1940s and 1950s the walkie-talkies and speedboats changed the odds against the poachers, as did the introduction of heavy fines. Any fish that were caught were usually sold to hotels in Galway.

This apparently easy way of making some extra money did not always have a happy outcome. One man, Michael Murphy, was sent to jail even though he was innocent, and more tragically John Duggan, a young poacher, died at Curraghmore trying to evade the Gardaí.

Local poetry about Clare

The River Clare is an important and unique local amenity and a defining feature of Claregalway. Its symbolic significance is relayed in this poem by Edward Coppinger, composed in 2013:

Ode to the River Clare

Are you still there aflowing

With Connaught blackwater you drain,

That I loved so much agrowing

My Clare I won’t see again.

On your banks often went rambling

’Twas mostly daydreaming in truth,

Escaping during my wandering

With a mind of untroubled youth.

Often I sigh for times gone by,

Of the things you meant to me,

And over the wide world would fly

To the Danube, Rhine and Yangtze.

Once in a while you’d be the Nile

Winding its way to the sea,

When a child myself I’d beguile

That you were also the Mississippi.

By the great Nile I once served awhile

In an oven known as Khartoum,

With good lads of rank and file

Wishing I was in Cahernahoon.

And held the line of dear father Rhine

That Romans did long before,

Drinking glasses of German wine

Yet pining for the bridge of Cregmore.

The Danube isn’t blue to behold

As through the Balkans it sweeps,

Oh I’d prefer to be dressed in old clothes

At Corbally washing the sheep!

Learning to swim in your water,

Hawthorn bushes my changing room,

Useful on the beach of Gibraltar

While secretly wishing ’twas Tuam!

We will meet once again river Clare,

When my time in this world passes,

My soul to some place elsewhere

But your water will get my ashes!

May the wild wind be my dead march,

And lapping water the very last song,

Drifting under that old bridge’s arch—

On your blackwater borne along.

Memories from reader Bernadette Redmond

The Clare River that ran near Bina’s Pub and the 13th century Friary ruins were a big attraction for us children being a glorious place to play. We used to lie on the memorial slabs pretending to be dead or looking up at the ever moving clouds talking or dreaming, or playing hide and seek ignoring the notices not to climb. Keep away from the River was a cardinal rule but to circumvent suspicion we could use the legitimate excuse that we were going to the graveyard to pray for our family dead, and to weed their graves and with only the rooks to spy on us we got away with murder. Dusk called us home because not only did we have the Bean Sí to worry about but blood sucking bats in the bell tower as well. Our bats were probably the common pipistrelle or the lesser horseshoe but Dracula had a lot to answer for back then.

Going out the side gate of the Friary led to the river bank where we fished in the reeds for pinkeens, floated sticks and paper boats downstream or searched for animal bones from dead sheep. I loved watching the elegant gliding swans on the river, gazing on them wondering if any of them were descendants of the Children of Lir. Fishing for pinkeens, or minnows, required jam jars containing a piece of bread that were sunk gently to the river bed, then pulled up again by two pieces of string around the neck to keep it steady, and not disturb any pinkeens that had gone inside to nibble the bread. The jars we borrowed from Bina who has never scalded a jam jar in her life, and who, if she made jam, would probably have emptied any surviving pinkeens out of them and poured in the jam.

Keeping our clothes dry was an overriding preoccupation. A visit to Bina’s kitchen we could get away with, if my cousin Maureen didn’t tell tales. Being the only one of us with a conscience and suicidal tendencies, she didn’t realize that confessing to Aunt May didn’t automatically get you a free pardon. Aunt May’s version of justice was one of joint enterprise, “you participated and/or didn’t stop what was going on—ergo you were an accomplice and guilty by association.” Her not guilty verdicts were zero.

Wet clothes were a dead giveaway. The girls therefore tucked their dresses into their knickers, and my cousin Tommy rolled his short pants as high as they would go. There was a strict no splashing rule, however if the worst came to the worst we knew that Bina would dry our clothes in front of her hearth, because, despite Aunt May’s dire warnings we never passed by without a visit to her kitchen.

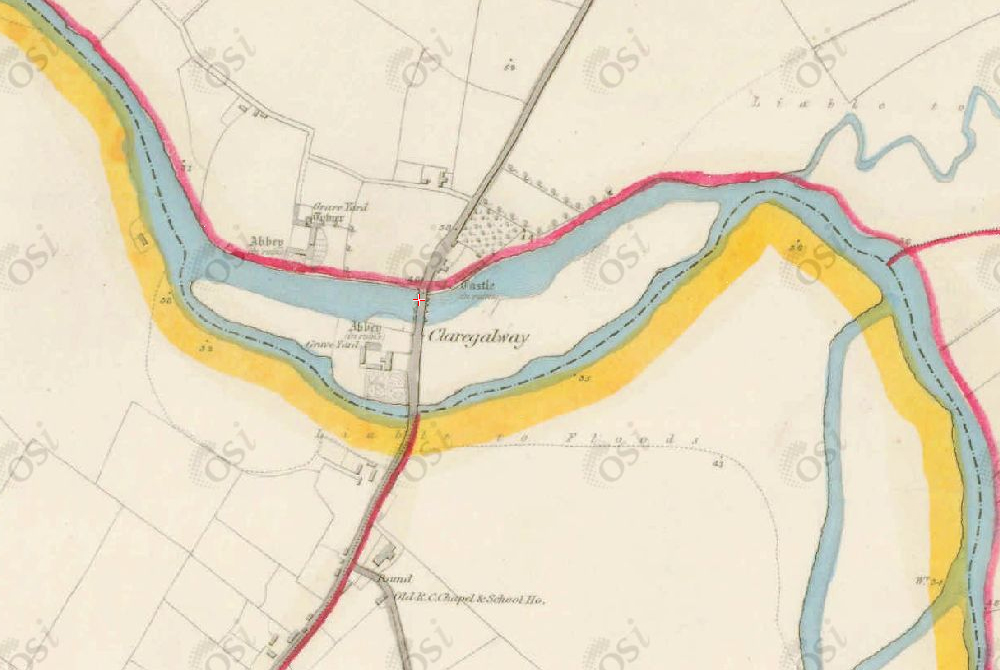

- This map (from the 1830s) shows how the Clare used to flow beneath the Nine Arches. The Arches Hotel currently sits where the yellow line meets the main road.

- Compare the image above to this satellite shot from 2005, which shows a much tamer Clare, and a large amount of construction on her flood plain.

- The River Clare slips by the Castle and the Friary (above) before continuing to Lough Corrib.

- Pictured is River Oaks housing estate, with An Mhainistir in the background, mirroring the curves of Clare as she passes under the N17.

- In late November 2009, Claregalway experienced its worst flooding in recorded history. Many homes were destroyed after torrential rain caused the Clare to rise and burst her banks.

- Another photo from the floods of November 2009. The N17 was impassable for two days, during which time many members of the community came together to help those effected.

- Although salmon isn’t as plentiful as it once was, fishing is still a popular activity by the Clare.

- This undated photo shows farmers bringing the turf home from the bogs in Montiagh North. This would have been a familiar sight during the 19th century, but flat-bottomed boats like those pictured above no longer operate on the Clare.