06 Apr 2020

- David KnowlesDigital Media Specialist, World Economic Forum

World vs Virus PodcastListen now on SpotifyMost PopularHow does your immune system work?Phil Cain 07 Apr 2020These photos show China’s national 3-minute silence, to honour those who have died from coronavirusAlexandra Ma · Business Insider 05 Apr 2020Coronavirus could trigger biggest fall in carbon emissions since World War Two – but any decline could be short-livedShadia Nasralla, Valerie Volcovici, and Matthew Green · Thomson Reuters Foundation trust.org 04 Apr 2020More on the agendaExplore context

COVID-19Explore the latest strategic trends, research and analysis

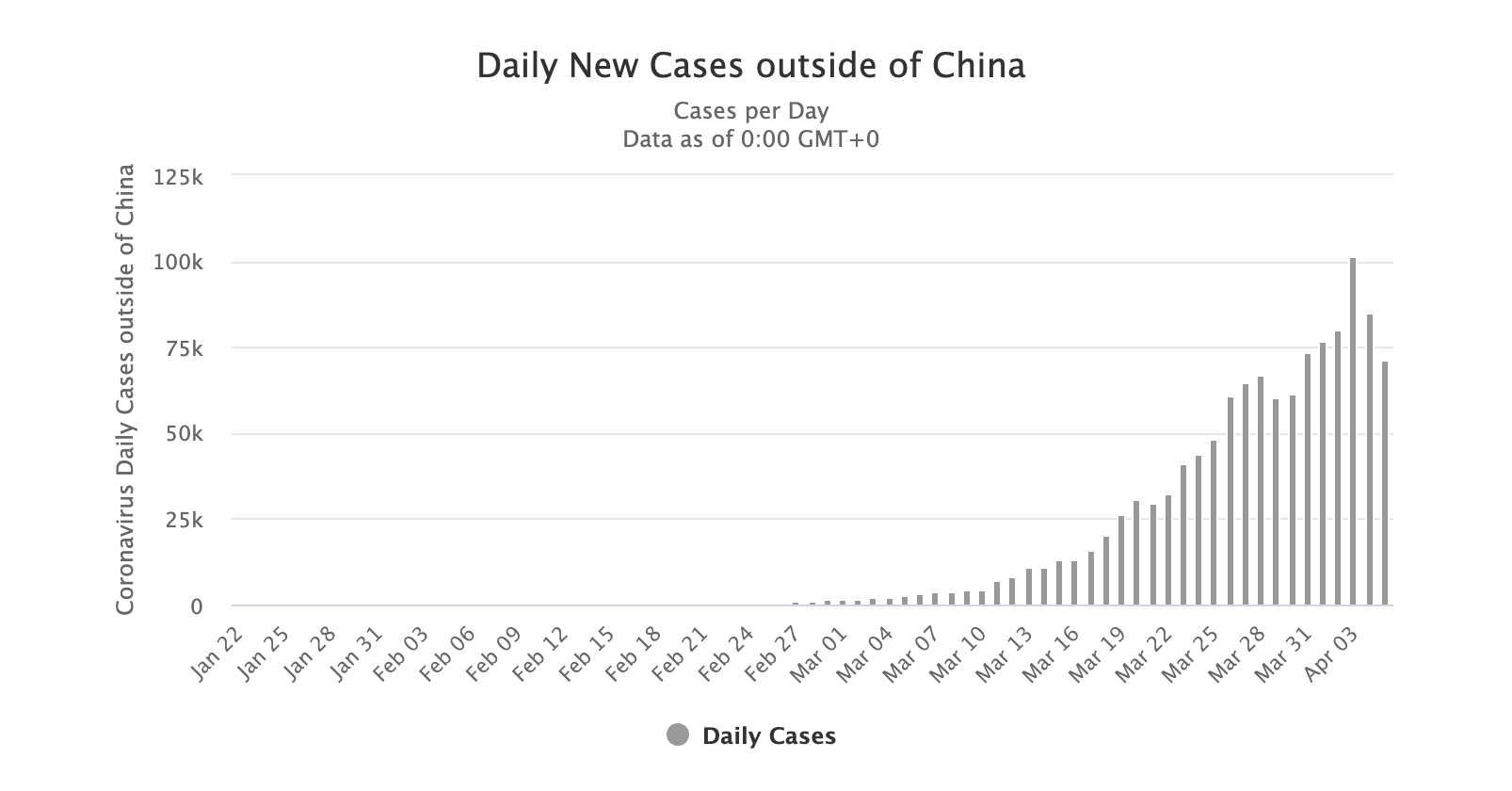

- We may be approaching a saturation point in terms of coronavirus infections in some of the worst-hit countries.

- Eventually, the virus will run out of people to infect.

- But there are still many unknowns when it comes to this virus.

More than one-third of the world’s population is now in lockdown as the world battles the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.

We spoke to Belgian virologist Guido Vanham, the former head of virology at the Institute for Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium, and asked him: how will this pandemic end? And on which factors might that depend?

Have you read?

- Has Italy’s coronavirus outbreak finally peaked?

- Track the spread of coronavirus around the world

- How can we save lives and the economy? Lessons from the Spanish Flu pandemic

How will this pandemic end?

Guido Vanham (GV): It will probably never end, in the sense that this virus is clearly here to stay unless we eradicate it. And the only way to eradicate such a virus would be with a very effective vaccine that is delivered to every human being. We have done that with smallpox, but that’s the only example – and that has taken many years.

So it will most probably stay. It belongs to a family of viruses that we know – the coronaviruses – and one of the questions now is whether it will behave like those other viruses.

It may reappear seasonally – more in the winter, spring and autumn and less in the early summer. So we will see whether that will have an impact.

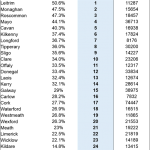

But at some point in this epidemic – and certainly in the countries that are most affected, like Italy and Spain – there will be saturation, because according to predictions, up to 40% percent of the Spanish and 26% of the Italian population are or have been infected already. And, of course, when you go over 50% or so, even without doing anything else, the virus just has fewer people to infect – and so the epidemic will come down naturally. And that’s what happened in in all the previous epidemics when we didn’t have any [treatments]. The rate of infection and the number of those susceptible will determine when that happens.

What are some of the factors at play? What do we know, and what don’t we know?

GV: The first thing we know, of course, is that it’s a very infectious virus – that’s probably something that every inhabitant of the world knows. But what is not known is the infectious dose – how many viruses you need to produce an infection – and that will be very difficult to know unless we perform experimental infections.

And we know people develop antibodies. That has been clearly shown in China, but we are not yet sure how protective these antibodies are. There is no convincing evidence yet that people who have recovered get ill again after a few days or weeks – so most probably, the antibodies are at least partially protective. But how long will that protection last for – is it a matter of months or years? The epidemiology in the future will depend on that – on the level of protective immunity that you get at the population level after this wave of infections, which we cannot really stop. We can mitigate it, we can flatten the curve, but we cannot really stop it because at some point we will have to come out of our houses again and go to work and school. Nobody really knows when that will be.

The virus will take its course and there will be a certain level of immunity – but the answer to how long that will last will determine the periodicity and the amplitude of the epidemics to come. Unless, of course, we find a way to block it in a year or so from now with an effective vaccine.

There is also an unresolved question about what determines an individual’s susceptibility to this disease. Of course there is age, but that’s not so surprising. People’s immune systems weaken with age. But then there is this concept of co-morbidities, which means that some people, even younger people, get ill because they have other diseases.

It’s logical that when you have cancer or diabetes, that you are more susceptible to infections. But what is remarkable – what we do not really understand – is that people with simple hypertension are also very vulnerable to developing this disease. So that’s one of the unresolved questions.

And it will be interesting to see what the profile is of people who are infected but do not get ill. We will know in a few months – that question is already being addressed in China. Then you can go back and test for antibodies, because it looks as though everyone who has gone through the infection will develop antibodies – and that those will remain for a while.

There are people that have antibodies and have not presented to to the medical services and claim that they have been healthy all the time. What’s the genetic profile of those people as compared with the people who went to the medical wards? That is an interesting question. One hint has already been discovered in China; your blood group could be important. It’s very preliminary data, but in a year or so from now we will have a lot of data on that as well.