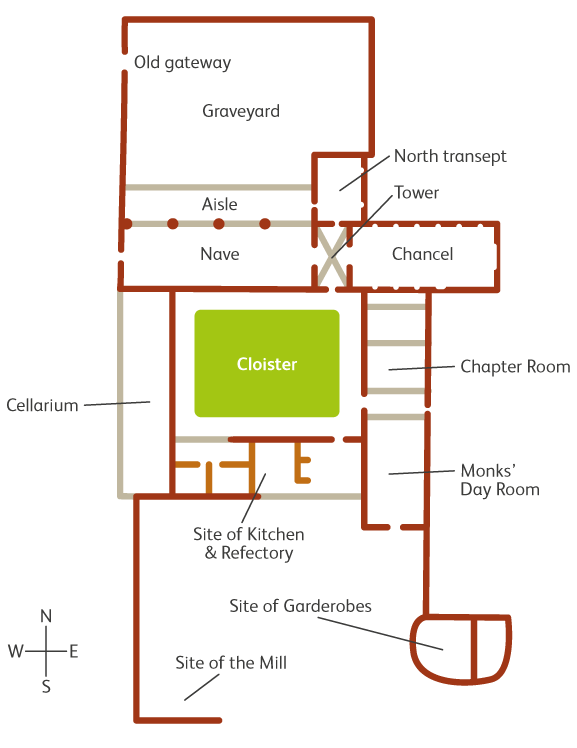

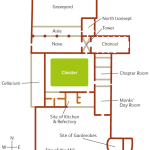

- This ground plan of the Friary is based on one drawn up in 1892 by the Commissioners of Public Works.

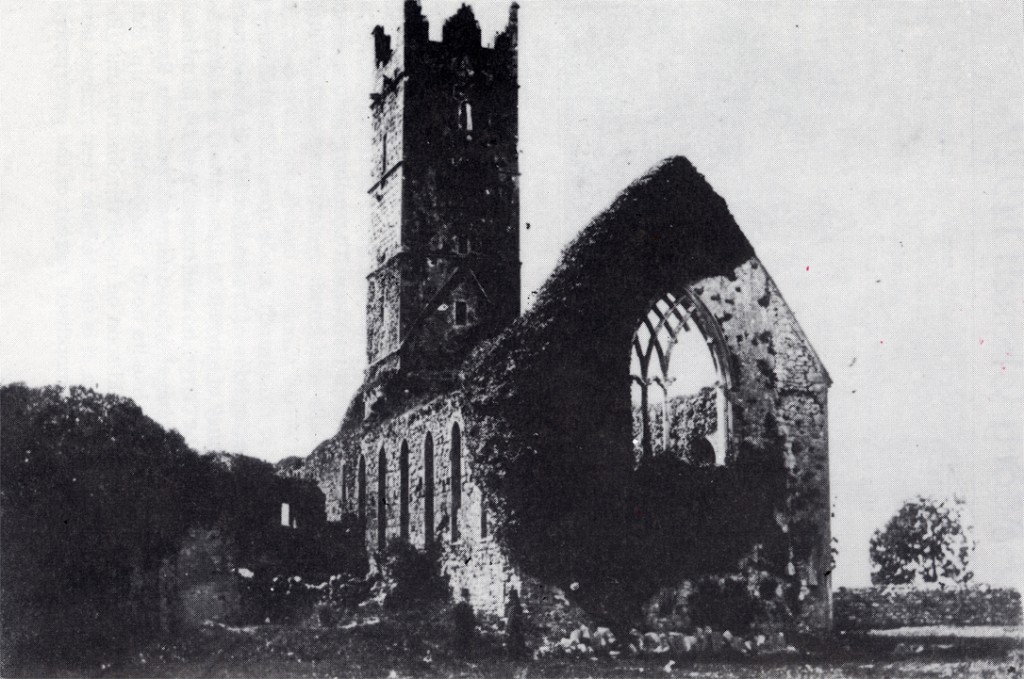

- The east window is the largest and most elaborate in the building. It was added in the 15th century, replacing earlier lancet windows, and was repaired (after centuries of damage) in 1899.

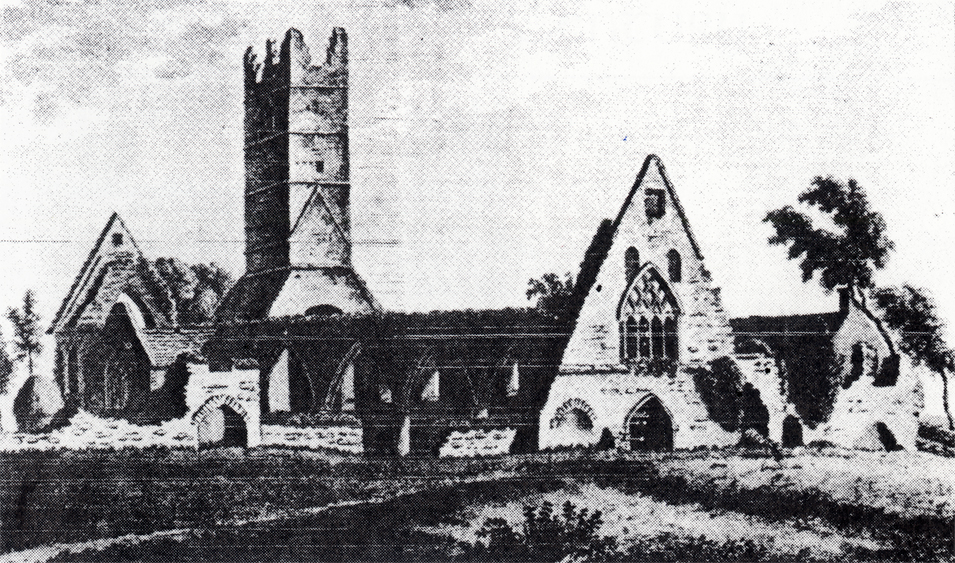

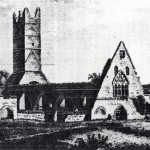

- The above drawing, made from the north-west, is from Francis Grose’s The Antiquities of Ireland, 1792.

- The north transept arouses the most interest of a nostalgic kind. It was used as a place of divine worship for over four hundred years, defying ruination and desecration until the 16th century, after which it was despoiled again in 1650 and 1798. It was in use as a chapel for an annual Mass until 1910.

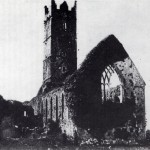

- The Friary tower viewed from the cloister.

- A rare view from inside the tower of the Abbey. The tower is currently inaccessible, though may once have been used as a storage loft.

- The cloister used to have a large arcade window (visible in the 1792 sketch above), but this has now vanished. The remains of corbels and the spring of an arch at each angle inside the cloister show that diagonal ribs crossed the walk at those points. It also used to have a lean-to roof.

- Outbuildings include the remains of a water mill (above), which used to sit alongside the River Clare but is now about twenty feet north of it. The “raised spot” which is designated ‘site of garderobes’ in the ground plan (top), used to be a small cottage and gardens, “made for pious meditation… the river murmured pleasingly near the garden in front.” (Walks Through Ireland by John Bernard Trotter, 1817)

- A view of the Friary from the north-east, with the sun setting in the background.

- This photo pre-dates the conservation work begun in the 1890s when the Friary was entrusted to the care of the Commissioners of Public Works. The damaged east window was repaired and the ivy-clad gables were stripped as part of works “at a cost of about £200” at the end of the nineteenth century. (Commissioners of Public Works Annual Report, 1900–1901)

The Friary is undoubtedly the most notable landmark in the parish of Claregalway, withstanding the ravages of time, weather and man for almost eight hundred years.

It provides a very visible reminder of our heritage and religious tradition. The annual ‘Cemetery Sunday’ helps to maintain this tradition, but the Friary is open to the public all year round. When one walks in the cloister courtyard, with the River Clare flowing gently in the background, one can escape the hustle and bustle of modern life and the constant noise of traffic on the N17. Here one can achieve a sense of peace and tranquility. It is an important and unique amenity that is available to the local community and is neatly complemented by the nearby Castle and Nine Arches bridge.

Architecture

The Claregalway Friary building, like most other friaries in Ireland, is composed of two main parts:

- The church, including the tower.

- The living quarters, including the cloisters.

Church

A cruciform church is shaped like a cross. The nave and the chancel are like the upright beam of the cross, while the transepts form the arms of the cross. The transepts run north and south from the point where the chancel joins the nave, and the tower marks this point. However, the church in the Friary does not have a south transept.

This church is basically rectangular shaped and like most churches of the period was built facing east, with the altar on the eastern end. The total internal length of the structure is 142 feet. The original church was built in the early pointed style of the thirteenth century. The tower, the east gable window and the north transept were added in the fifteenth century.

Chancel

The chancel refers to that part of the church, near the altar, which was reserved for the clergy and choir and is on the eastern end. It is 52 feet long and 23 feet wide. There are six tall narrow pointed (Gothic style) windows in both the north and south walls that provide light; each window is 2 feet in width and 11 feet in height.

Also there were originally three pointed windows in the east gable, but these were replaced by the present one in the fifteenth century that reflected the elaborate ornate style of that time. This east window is the crowning glory of the church. Mullions or vertical stone shafts divide the window into five lights or sections with very gracefully proportioned patterns in the upper part of the window.

On the south wall of the chancel are the remains of a piscina, which is a stone basin in which the chalice used in the Eucharist is rinsed, and the sedilla, a group of three seats let into the wall for the clergy performing the service. The De Burgo tomb, with the arms and crest of the De Burgos, stands in the north side wall, the position in which the founder or other great benefactor’s tomb is generally placed.

It carries the following Latin inscription:

Husc Incum sibi elegit Dus Tho Burgo de Anbally, Fils Richarde de Derrymaelaghni Anno Domini 1648

In translation:

Thomas de Burgo of Anbally, son of Richard of Derrymacloughney chose this place for himself, 1648 AD

Nave and Aisle

The nave is the main part of the church; it is on the western end and was where the congregation and laity sat. It is 72 feet long and 23 feet wide. The word nave comes from the Latin word nave, meaning a ship, for the ship was thought to be the symbol or sign of the Christian church, which carries believers over the sea of life into the safe harbour of heaven. Almost the entire western gable end is no more.

An old 1792 sketch of the Friary (see photo) shows an elaborate window with four sections interlacing with round pieces over the heads. The people’s main entrance was by a large door in the western gable, of which the outline can just barely be seen. The western gable together with the door and window collapsed sometime in the 19th century. There are several sedillas on the south wall; the broken arch of one has been repaired with small red tiles.

There was a north aisle, with a width of 11 feet, which was separated from the nave by an arcade of four pointed arches on cylindrical pillars. The Romanesque style, rounded arch, connected the aisle with the north transept. Unfortunately this aisle is now demolished.

North transept

This measures 25 feet long by 16 feet. There is a doorway from under the tower into the transept chapel that would have been used by the clergy. However the public had access from the then north aisle of the nave through the arch. Its north window has three shafts with interlacing heads and the two windows to the east are richly carved like some of the window heads in St. Nicholas’ church in Galway. The chapel has an altar and altarpiece, and also a piscina near the door. The arch had been closed and the north window blocked, when the friars had earlier modified the transept to serve as a penal day chapel. Also it had been unroofed around 1915 by the Rev. PJ Moran.

Father Martin Blake, the Friary’s Guardian in 1798, “had a small chapel formed out of [this] part of the old abbey, roofed in, and adorned with simple, but not inelegant taste… In the unhappy times of 1798, it had been ruined and defaced by some English militia, though Mr Blake had given all his provisions to the soldiery. ‘I may live to repair it, and I pardon them’, was all his remark.” (Walks Through Ireland by John Bernard Trotter, 1817)

There is a tablet affixed to the wall of the chapel to the right of the entrance under the tower which carries the following Latin inscription:

Quisquis eris, qui transieris, Sta, Perlege, plora, Sum qd. eris, Fueramq. qd. es, Pro me, Precor, Ora, P.M.B. o.s.f.

In translation:

Whosoever you may be who should pass by, stop, read thoroughly, mourn. I am what you shall be and I was what you are. I entreat that you pray for me, F(ather) M(artin) B(lake). O(rder) (of) S(t). F(rancis)”.

The plaque measures 28 inches by 7.5 inches, is not dated, and may mark Fr Blake’s burial place.

Friary tower

The tower or belfry was built about 200 years after the original building and within the walls of the church. It rises in three stages above the roof, to a height of 80 feet from the ground level. The insertion of this prominent tower blocked up one of the clerestory windows of the nave and an adjoining window seems to have been taken out and a larger two section window put in its place, to compensate for the loss of light. It is built on arches or a groin type vault supported by four massive piers.

The huge corbels (projecting stones) in the belfry piers were probably for the support of a roof beam. If you look very closely, you’ll see four small stone heads on each pier and one in the centre of the roof vault. Also near the centre of the roof vault, you’ll see two small round holes, through which ropes may have been threaded to allow the friars to ring the bells from below.

The windows in the bell storey of the tower are normally the largest to allow free egress to the sound of the bells. These windows have two sections with transoms (horizontal bars) to strengthen the mullions (vertical shafts) and perhaps to enhance the appearance. The tower roof was probably a pyramidal shaped spire crowned by an outsized iron cross.

There is an opening or little doorway in the south wall of the tower within the roof space of the church, which may have been constructed for ventilation purposes or to effect repairs. It may suggest that there was some sort of loft or attic overhead although there is no evidence of a practice of arranging living quarters over the church as that would imply a lack of reverence. This doorway was approached by way of another doorway over the northern lean to of the cloister wall, which was in turn approached from the north of the east dormitory. Today the tower looks very tall because the church is no longer roofed, thus giving it extra visibility.

Cloister

On the sheltered, sunny, south side of the church is the cloister. The cloister is the rectangular open green space, which is surrounded by a path—this path used to be covered with a lean-to roof. This lean-to provided shelter from the rain for those passing from one part of the friary to another. The cloister enclosure measures 57 feet by 72 feet.

The living quarters was composed of dormitories, kitchen, refectory or dining area, chapter room and a monk’s day room. The building to the east of the cloister seems to have abutted against and obstructed the light of three of the church chancel windows. The upper portions of this contain the dormitories.

Also this building shows signs of frequent changes. There are traces of three built up openings onto the cloister that probably formed the entrance to the chapter room. There are three stories in the monks’ day room and in the south wall on the upper floor, there is a large open fireplace, at the back of which externally is a built up window. The buildings south of the cloister also show signs of frequent changes. It is possible that the friars who inhabited the monastery in the eighteenth century occupied this portion only, which was changed to suit the needs of a small community who sought refuge in the ruins.

Outbuildings

There was probably a water mill about twenty five yards to the south of the friary. Also there are some obscure remains of a building about thirty five feet south-east of the friary between it and the Clare river and located on what is designated ‘site of garderobes’ at the lower right hand corner of the accompanying ground plan. It’s reached by steps leading from the north and from the south. A water channel probably flowed alongside both of these buildings.

Timeline

13th Century

The history of the foundation of Claregalway Friary is obscure, like most other friaries. The founding had been generally ascribed to approximately the year 1290. However in 1956, the chance discovery of a thirteenth century document in the State Paper Office in London had the result of “bringing the date of the foundation of the Franciscan house at Claregalway to some year between 1250 and 1256, thirty years before the date commonly given hitherto”.

John de Cogan I, one of the early Normans, built the monastery for the Franciscan friars around 1252 in what was then called ‘Clár an Dúil’. Claregalway had been granted to John de Cogan as a reward for his part in the conquest of Connaught. The Normans were major patrons of the church and played a large part in the introduction of religious orders. ‘Clár an Dúil’ or Claregalway was considered to be in the diocese of Annaghdown. The Friary is reputed to be the first known Franciscan House in Connaught.

In 1291, Pope Nicholas IV issued a bull granting an indulgence of one year and one quarantine (old English for forty days) to all penitents who visited the church of the friars minor of Claregalway on certain feast days. Those were the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin, St. Francis, St. Anthony, St. Clare, or during their octaves, as well as on the anniversary of the dedication of the church.

In 1297, the Franciscan Friary was at the centre of an ecclesiastical dispute between the diocese of Tuam and Annaghdown that reached the courts of King Edward I and Pope Boniface VIII in Rome. The diocese of Annaghdown had been created before the coming of the Normans and had the support of the native Gaelic O’Flaherty family, while the Tuam diocese represented the Normans. The Archbishop of Tuam considered that the territory of Annaghdown, or at least part of it, properly belonged to Tuam.

While the Bishopric of Annaghdown was vacant, its ceremonial items such as the mitre, crosier, ring, sandals together with letters and documents detailing the apostolic privileges were left for safekeeping with the friars of Claregalway. William de Bermingham, Bishop of Tuam, raided the friary. His Archdeacon, Philip de Blund, had to appear before the court of common pleas in Dublin, charged with seizing forcibly from the Claregalway friars the chest of the Bishop of Annaghdown. And that “he broke it open in the doorway of the mother Church, and with force took away the episcopal mitre, with the pastoral staff and other contents.”

This dispute seems to have dragged on for a number of years. There is a record of the case being heard before the Chief Justice in Dublin in 1300. In 1303, Pope Boniface VIII ordered the Bishop of Limerick to effect an agreement between the Archbishop of Tuam and the Dean of Annaghdown and failing this to report to the Pope, however it is not known how this concluded.

14th Century

In 1327, John Magnus de Cogan gave to the guardian and friars of the convent “all the lands and tenements in Clonmoylan as far as Claredoule.” There is a picturesque condition imposed on the friars in return for this gift of presenting a rose annually to the donor and his heirs on the feast of St. John the Baptist.

In 1328, Robert, Bishop of Annaghdown sued Malachy, Archbishop of Tuam at the justices of the bench in Dublin for having by force carried off his goods and chattels found at “Strothyr Clare” (Claregalway) to the value of £40.

In 1333, another benefactor Philip Hamlin gave ten acres of land to the friars to provide the bread and wine for their Masses.

In 1368, Thomas de Bermingham, Lord of Athenry, gave them all the lands from Clonmoylan to Clare to pay for wine and candles for the altar.

In 1386, John Roch granted the friars as a perpetual alms all the lands of Clonmoylan, also an Alice Kerry bestowed on them two tenements and two and a half acres of land.

In 1387, Joanne Brown gave them more land. Also a James Caer, dean of the diocese of Tuam, gave them six acres of land at Cloynbiggan. (This could be the earliest reference to the present day address of “Cloonbiggen!”)

15th Century

Pope Martin V in March 1426 addressed a mandate to Cormac O’Callaghan, a canon of Annaghdown, in answer to a petition almost certainly sent to him by a Claregalway friar. This mandate authorised him to grant dispensation to a friar named William Pulard from an irregularity incurred by him. The offence was: “that William being then a priest, when playing with other clerics and laymen a game customary in those parts among both seculars and religious, accidentally struck another player, Donald O’hAschí, layman, near the ear with a sharp pointed stick, from which wound, Donald, a year later, owing to his own and his surgeon’s carelessness died.” Also, “if this poor friar was on his knees all this time over the death of this poor man, which was by accident, if the facts were as stated, then the Parish Priest here was to rehabilitate William Pulard and dispense him and allow him to minister again.”

In 1430, William de Burgo, with the consent of all the citizens of the town of Clare, granted them the pasturage of twenty-four cows in the common pastures of the town.

In 1433, Pope Eugene IV granted an indulgence of four years and four quarantines to all the faithful who visited the Franciscan church of Claregalway, chiefly, it would seem, to encourage the people to contribute to the renovation of the church and the completion of the steeple.

16th Century

Two great waves of destruction were responsible for the ruined state of most abbeys and churches in Ireland, including the Claregalway friary. The first was brought about by the suppression of the monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII and the second associated with the Confederate wars and the ensuing invasion by Oliver Cromwell.

On the 11th July 1538, Henry VIII sent Lord Leonard Gray to Galway. It is recorded that the abbey of friars at Claregalway was rifled by Gray’s troops on their way to the western capital and “neither chalice, cross nor bell left in it.”

By 1541 most of the monasteries were closed, their possessions confiscated and their communities scattered into the surrounding countryside. The monasteries were scavenged for anything of value: lead, glass, timber and slates.

Queen Elizabeth I granted the abbey, with all its appurtenances (belongings) to Sir Richard de Burgo in 1570. However the friars remained in or near the place until about 1589 when Sir Richard Bingham, the English governor of Connaught, cleared the actual building of its inmates and used it as a barracks. According to undoubted tradition, he stabled his horses in the monastery chapel, while his soldiers were quartered in the cloisters.

17th Century

King James confirmed the title of local lords who obtained church lands following the confiscations of the previous century. The Earl of Clanrickard was given the “the late monastery of Balleclare (Claregalway), with the site, church and church yard, 6 cottages and gardens, 24 acres arable, common pasture for 24 cows on the commons yearly, and a waste water-mill…”

After the commencement of the civil war in 1641, the Franciscans made an attempt to restore the buildings, but owing to the turbulence of the times, were unable to carry out their intention.

18th Century

Edward Synge, The Anglican archbishop of Tuam, wrote on 25 November 1731: “There is a Friary in Claregalway, where three at least are always resident”. Stratford Eyre, the High Sheriff of the county, in submitting his report in 1732 stated: “The friars of Claregalway live close to the Abbey and are building a large house. It is the estate of Thomas Blake.”

In 1791, Coquebert de Montbret, who was then the French consul at Dublin, recorded in his journal that at Claregalway “The monks are settling down among the ruins.”

19th Century

According to a tabulated list of houses in the province, compiled by Fr J.J. Mullock. OFM, in 1838, the community in Claregalway then numbered two preachers; neither the chapel nor residence had been constructed within the previous decade. Also according to the Complete Catholic Registry for 1845: the community in Claregalway then consisted of but two members.

The difficulty of maintaining the friary in such difficult circumstances had become a very real one for the Irish Franciscan province. Overall numbers had been decreasing steadily, from about 220 members in 1766 to about 150 in 1782, chiefly it would appear, as a result of restrictions imposed by the authorities at Rome in 1751. Of the 36 houses that were occupied in the year 1800, only 16 were still open in 1837, and these were staffed by a total of about 55 friars. It was therefore inevitable that a small foundation such as Claregalway could not continue its separate existence because it was situated in a rural area about 6 miles from Galway, which had its own community. There were just not enough personnel available to staff it.

It would appear from a newspaper report in the Galway Vindicator on November 1847 and supported by a local account that the community ceased to reside at Claregalway friary during the month of November 1847. The account states:

“One day, one of the two friars who were the last to reside at Claregalway, having been questing for contributions for their support felt himself become ill and, instead of returning to Claregalway, asked the driver of the pony-trap to convey him to the friary at Galway. The driver complied and on his return to Claregalway, informed the other friar, who thereupon said in grief, ‘That means that I too must leave here.’ On the following day the driver brought him also to Galway.”

The friar who took ill was Fr James Hughes and the other friar was Fr John Francis.

However on feast days, friars used to come from Galway to Claregalway to celebrate Mass, hear confessions and preach there. From the year 1860 not even these services took place. Guardians continued to be appointed up to about 1872. This however does not necessarily indicate that a community had again taken up residence there, because ‘titular’ or nominal guardianships were traditional, and at that time were numerous in the Irish province of the Order. They were particularly valued for the right of voting at chapter meetings that they conferred.

The Franciscans did not own the friary as such since it had been given to the Clanrickard family early in the 17th century. There is a receipt dated 16th January 1872, which records the payment by the then guardian at Galway of the sum of £9–9–8d, “being one year’s rent due to the Right Honourable Lord Clanmorris up to the first day of November 1871, out of his holdings in the Abbey, Claregalway”.

On the 21st September 1892, the building that was then in the possession of Lord Clanmorris was vested in the Commissioners of Public Works, under the provisions of the Ancient Monuments Protection Act of that year.