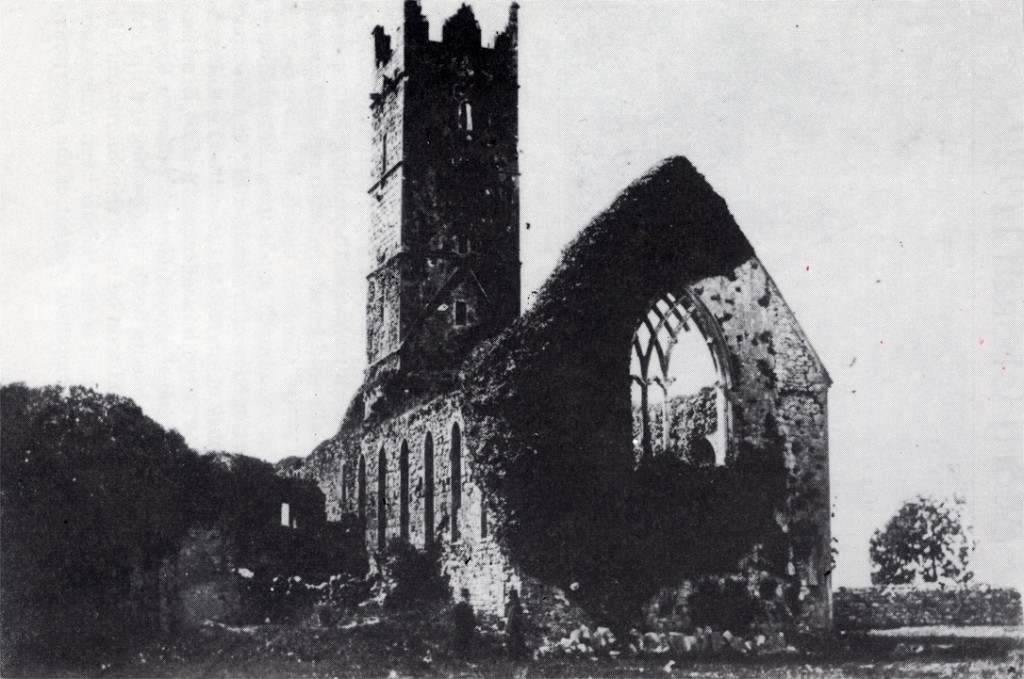

Perhaps the most notable landmark in the parish of Claregalway lies just to the north of the river Clare and to the west of the Norman castle. This is the Franciscan Friary which has been in existence since the 13th Century. A certain amount of debate has been held regarding the actual year of construction and the generally accepted year was 1290, the erection being credited to John de Cogan. This man was in fact a descendant of Milo de Cogan, reputedly the first Englishman to set foot in Connacht, but who ended up making a shameful retreat.

However, evidence was recently uncovered which makes the Friary at least 40 years older. A deed from 1252 mentions the Friary and it is known that between the years of 1250 and 1256 lands were given to the friars in Claregalway. The Friary is also reputed to be the first known Francisan house in Connacht and it was known to be under the custody of Nenagh in a document from 1260. This earlier construction date is also accredited to John de Cogan, so it is obvious that he was involved, regardless.

Two events of note closed the history of the Friary in the 13th Century, both involving different popes. In 1291 Pope Nicholas IV offered an indulgence to anyone visiting the Friary on certain feast days. Religion was also the cause of events involving Pope Bonifact VIII which centred around an unsettled quarrel over whether or not Annaghdown was in the Tuam archdiocese. Fearing the worst Annaghdown’s Bishop sent all the pontificalia or symbols of office to the Claregalway friars for safe keeping. This keeping lasted until 1297 when Philip de Blund acting under orders from Tuam, violently removed the items.

In 1327 a descendant of John de Cogan, going by the name of John Magnus de Cogan lived up to his name by giving a large endowment to the Friary. He was credited as both a founder and a benefactor. Also in this century the friars were given lands by various other benefactors. They were to use these lands to pay for the expenses for bread, wine and candles. Later, William de Burgo gave them pasturage of 24 cows in a commonage. At this time we know that the friars were part of the community because of an unfortunate incident during a hurling game in the parish when a friar seriously injured a man who later died from his injuries.

In 1433, Pope Eugene IV granted an indulgence of four years to anyone visiting Claregalway Friary. This was an effort to raise money to renovate the church and also to complete the unfinished steeple. The Friary prospered from this time until 1469 when O’Donnell in his attack on the de Burgos burned much of Claregalway.

The next century proved to be a difficult one for monasteries and friaries in Ireland as in 1536 the Reformation Parliament came to the fore in England and Henry VIII was recognised as the head of the Church in Ireland. At this time then many monks and friars gave in and left their monasteries to ruin, the stone being used to build big houses. Claregalway Friary survived this period and its future seemed guaranteed under the reign of Queen Elizabeth when she granted lands in Connacht to Sir Richard de Burgh, who declared loyalty to her. However, towards the end of the 16th Century the land was back in the Queens name again. At this time,the Spanish Armada was to dock at Galway Bay and thus an army of the Queen, led by Sir Richard Bingham arrived into Connacht. He took over the Friary and converted it to a barracks going so far as to stable the horses in the chapel. The troops defaced the Friary and drove the friars away.

The friars attempted to restore the Friary in 1641, the year in which Civil War broke out in Ireland, and after this restoration the friars moved back in. Mass is known to have been said in 1643. Two years later their first guardian Peter Tiernan was appointed. In documents relating to this time the Friary was known as Coventus de Clare. Cromwell arrived into Ireland and in 1652 as his troops were in Galway they destroyed many monuments. By 1657 everything bar the Church was destroyed, but the friars remained in the locality.

In the eighteenth century, the numbers in the Friary seemed very depleted, but there are some conflicting reports. A report from 1766 stated that only 5 permanent residents remained in the Friary and that 3 of these friars were advanced in years. This was an improvement upon the figures of 1731 which gave the population in the Friary then as a paltry 3.

These figures are at odds with two other sets for 1776 and 1782, in which the numbers of members are set at 220 and 150 respectively. The truth of these rather inflated figures seems to be questioned by the report made by Rev. Daniel Agustus Beaufort, the rector of Navan, also in the 1780’s, when he said that the Claregalway Friary was in ruins. Coquebert de Montbret found on a visit that the friars actually settled down in the ruins but whatever meagre comforts they enjoyed were short-lived when the English again decided upon the Friary as a base. This time the soldiers ruined the chapel and poor Fr Blake, the guardian of the time, had to prevail upon friends of his in the Waterdale area for shelter.

Despite this sacking of the chapel, by 1801 four friars had moved back to the Friary. Eight years later Rev. Kenny shut the church down and everyone had to move out for the restoration which took place in 1811. In 1815, Fr Blake, who had survived the English was re-appointed as guardian, but unfortunately he died the very next year. An interesting aspect to note at this time is that before this reappointment, a Fr Crampton managed the house for some time, circa 1814. He was not a Franciscan friar, but actually a Carmelite and because of his order’s habit he was regarded throughout Claregalway as An Bráthair Bán.

School resumed in the chapel in 1826 and the Sunday mass of the time attracted between 600–800 people, with 80–90 people attending daily mass. Sadly however, friar numbers dwindled until in the middle of that century only 2 remained. Prior to this, in 1832, a new diocese, Galway, was set up to include Claregalway so that it was in to Galway that the friars finally decided to go. A local man is reputed to have acted as “driver” for the friars; when the older friar took ill on his rounds he told the driver to bring him to Galway. This sad task done, our man returned to the Friary to pass on the news to the other who then said “I must go too”. Thus the last friar left the Friary behind.

The friars did not totally abandon the local people though and masses were said there into the 1870s. It was also at this stage that the appointment of guardians ceased. The last friar who had actually resided at the Friary died in 1858, a Fr John Francis.

Rev. Martin Commins, P.P. Claregalway of the time, celebrated an annual mass in the chapel from 1892 but Canon Moran P.P. and other priests, discontinued the service. Indeed Canon Moran thought little of the Friary describing it as both “Norman and Alien”, a throwback to the financial aid given by the de Burgo’s. The same priest later took some interest in the structure when some travellers found protection from the elements in one quarter of the Friary. The Canon had the roof in this portion torn down and the people were put on their way.

Happily today the Friary is seen by all as an important part of our history and it should suffer no more damage. Also, a yearly mass is now being said for all buried in the Friary and its surrounds, which is always well attended, hail, rain or shine.

This material on the Friary of Claregalway was a FÁS scheme research of some years back but neither the particular trainee author(s) nor the original sources used have been identified to date. It would be a pity though not to see it published.

Aodán McGlynn