Galway Advertiser

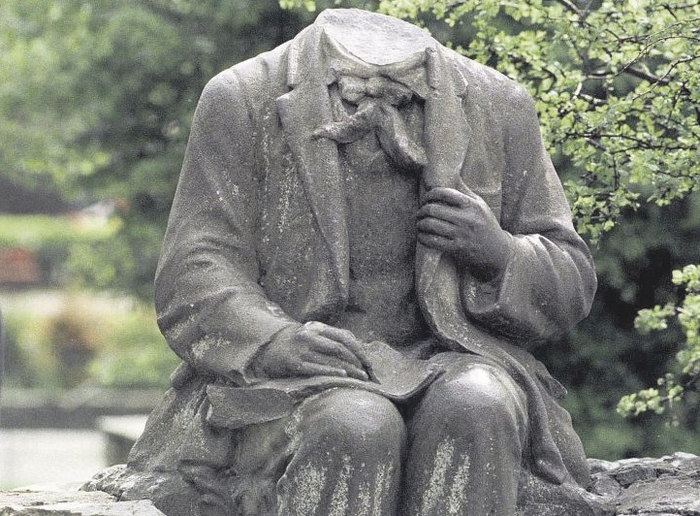

A postcard from the 1940s showing the Ó Conaire statue.

On October 6 1928, writer, journalist, teacher, and raconteur Pádraic Ó Conaire died in tragic poverty in Richmond Hospital, Dublin, at the age of 46. Since the turn of the century he had established himself as one of the leading lights of the Gaelic Revival, an innovative writer who pioneered the short story in Irish.

Born by the docks in Galway in 1882, and christened Patrick Joseph Conroy, he was the eldest son of middle-class Catholic merchant-publicans. Following the deaths of his parents, he was reared by extended family members in Connemara and west Clare before boarding at Rockwell College, Tipperary, and Blackrock College in Dublin.

In 1900, like so many young Irishmen of his time, Ó Conaire found work with the Civil Service in London. There, in the imperial capital, he joined the Gaelic League, which fostered his talents as a writer. A keen reader, Ó Conaire immersed himself in literature – particularly Russian, French, and Scandinavian – and was inspired to write short stories in Irish about the harsh realities of life on the Atlantic seaboard. His stories were first published in newspapers, winning numerous awards, and collections were published in book form to great acclaim. His audacious novella, Deoraíocht (Exile, 1910 ), cemented his fame.

Encouraged by his literary success, Ó Conaire abandoned the Civil Service in 1915 and returned to Ireland to pursue a career as a full-time Irish-language writer. His last important creative work was a fictional response to the 1916 Rising, Seacht mBua an Éirí Amach (Seven Virtues of the Rising, 1918 ). In the decade that followed, Ó Conaire wrote profusely but unprofitably, discovering that there was little demand in Ireland for Irish literature, other than for educational purposes. His final years were spent in poor health in Galway teaching Irish and writing for the Connacht Sentinel and other newspapers.

In the end, Ó Conaire was laid to rest in Bohermore Cemetery. In his relatively short lifetime, he published more than 400 short stories, six plays, and one short novel, as well as some 200 journalistic essays on a variety of topics. He influenced a generation of Irish writers, and even inspired Orson Welles to undertake a tour of Connemara by donkey and cart. Ó Conaire also became something of a legendary figure during his lifetime and fanciful stories of his ramblings and adventures abound.

Within a week of his passing, members of the Galway branch of the Gaelic League held a meeting in St Ignatius’ College, Sea Road. A memorial committee was established and a subscription card was issued requesting contributions, great or small, towards “placing a stone over his grave” or “founding a worthy memorial in his honour”. By 1930, more than £200 had been raised – about €14,000 in today’s money. The committee approached master sculptor Albert Power (1881-1945 ) who agreed to take on the project. This was a major coup as Power was a highly regarded and much in demand craftsman, who had been awarded several important commissions by the Irish Free State.

Power initially proposed he would carve a limestone portrait of Ó Conaire that would sit on a vacant plinth in Eyre Square. That plinth was formerly the base of a statue of Lord Dunkellin, a landlord’s son and former MP for Galway, which had been pulled down as a “symbol of landlord tyranny” in 1922. Power’s early sketches of the proposed statue were reproduced in newspapers in Ireland and the United States in order to further drive the fundraising campaign.

Power initially committed to having the work completed before St Patrick’s Day 1931 but, much to the dismay of the committee, the project took another four years to realise. The delay was due to the lengthy time it took to source a flawless piece of native limestone, which eventually came from a quarry in Durrow, County Laois. Power finally began carving the statue in November 1932. It was completed in February 1935, by which time he had decided against using the plinth, announcing Ó Conaire would instead be seated upon a rubble Connemara wall.

An interesting and unusual feature of the statue was that Power chose not to portray Ó Conaire as he was in his prime, instead portraying him as he was in later life, ravaged by his wayward lifestyle. In some ways, he presented the writer as he had depicted the characters in his stories – flaws and all. Ó Conaire’s eldest daughter visited the sculptor’s studio for an advance viewing, commenting that “the familiar expression of his face held me. Every time I looked up at it I saw my father.”

In March 1935, the committee decided to invite Éamon de Valera, Irish premier and advocate for the Irish language, to perform the unveiling. Interestingly, de Valera had attended Blackrock College with Ó Conaire and the writer had campaigned for him in the famous by-election in East Clare in 1917. The Irish premier was acutely aware of the symbolic power of such monuments, especially as the new State was trying to forge a post-colonial identity. In what was seen as an opportunistic move, he had unveiled Oliver Sheppard’s statue of the Death of Cúchulainn in the GPO, Dublin in April 1935 – the 19th anniversary of the Easter Rising.

The unveiling took place on Whit Sunday, June 9 1935, to a packed Eyre Square. The ceremony was conducted as Gaeilge and broadcast nationally on radio. De Valera used the occasion to speak about the Irish language and making Galway “the first city of the Gaeltacht”. An eagle-eyed passer-by had saved him some embarrassment by spotting and removing a blueshirt – the emblem of Dev’s opponents – that had been draped over Ó Conaire’s shoulders. Afterwards, de Valera attended the university to present an address commending its services to the Irish language and later enjoyed a play at An Taibhdhearc. It is sadly telling that a visit to Ó Conaire’s then-unmarked grave was not part of the official itinerary.

In the decades that followed, ‘Sean-Phádraic’ became iconic of Galway, one of its best-loved and most-photographed landmarks. When Eyre Square was modernised in the mid-1960s, the statue was relocated to a remote corner of the Square, but a public outcry soon resulted in its return to a more central position.

Over time, the statue began to show signs of wear and tear – one local councillor complained it was “like a magnet to the hundreds of children between the ages of five and seventy-five who sprawl all over this very fine piece of Irish sculpture”.

Tragically, the statue was decapitated in 1999 with the vandals attempting to leave the city with the head. Thankfully, it was recovered. In the court case that followed, the presiding judge remarked that “the attack had as traumatic an effect on Galway as the Mona Lisa being taken from the Louvre in Paris”. Although the statue was repaired, the reality was that its days outdoors were numbered. With construction works taking place in Eyre Square in 2004, the statue was moved to City Hall and two years later it was transferred to the new city museum.

While many have called for its return to Eyre Square, the fact is that it would be putting this work of art at risk of irreparable damage. Consequently, Galway City Council commissioned a replica in bronze. There are, however, many things to admire about the replica. The damages inflicted on the original have been repaired in the replica. The bronze finish brings out many features not as clearly visible in the original – such as the bird and rabbit at Ó Conaire’s feet. In a nice touch, the replica is to be seated on a wall of granite built from stone (kindly gifted by Jane Conroy, a relative of Ó Conaire ) from Garafin House in Rosmuc, where the young Ó Conaire was reared by his paternal grandparents. Visitors can always see the original at Galway City Museum.

Brendan McGowan is education officer at the Galway City Museum and co-author of Seacht mBua an Éirí Amach/Seven Virtues of the Rising, published by Arlen House in 2016. Photographs by kind permission of Galway City Museum, Tom Kenny and Phyllis Power.